Once you’ve failed to pay your mortgage, you begin to approach foreclosure. Foreclosure is like drifting in a small boat towards a waterfall. It might seem scary at first, but there are a few things you can do to avoid going over the edge. We’re going to break the long and varied process of foreclosure for you and go over a few different possible outcomes, so you know what to expect. Whether you’re reading this out of curiosity or you’re looking for clarification as you begin the foreclosure process, it’s best that we quickly review just what a mortgage is.

What is a mortgage again?

A mortgage is an agreement to pay back a loan with interest over a set period of time. If you fail to pay your mortgage, you fail to repay a loan and your debt still stands. Your lender will repossess your house in order to partly satisfy that debt. They can repossess your house because the house is the collateral for the loan.

Generally, there are two main types of foreclosures: Judicial and Non-Judicial Foreclosures.

Judicial Foreclosure

A judicial foreclosure is when the majority of the foreclosure process goes through the court system. To begin the foreclosing process, the lender has to file a lawsuit against the borrower. In this case, the borrower has the opportunity to contest the foreclosure in court before a judge. For some states (to be listed below), most foreclosures are judicial. Be aware that even non-judicial foreclosures can become judicial if the lender files a lawsuit against the borrower. It’s also important to know that the final sale in a judicial foreclosure happens through the courts.

States with mostly judicial foreclosures:

(Caution: Even some states that are judicial might have streamlined the foreclosure process)

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Hawaii

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Maine

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma (upon borrower’s request)

- Pennsylvania

- South Carolina

- South Dakota (upon borrower’s request)

- Vermont

- Wisconsin

Non-judicial Foreclosure

Non-judicial foreclosure is a foreclosing process where the lender is not required to go through the court system. This type of foreclosure is much faster than judicial foreclosures which can take a year or more to conclude because the borrower challenges the lender in court. A non-judicial foreclosure can take as little as sixty days or even shorter and concludes with a home auction done not through the courts, as with judicial foreclosure, but through a private third party.

A word of caution, in the U.S., foreclosure proceedings vary state by state and even within states. For example, in Florida real estate, all foreclosures must be approved by a judge and generally involve time in court and various legal proceedings.

By contrast, in Massachusetts real estate, which typically has non-judicial foreclosures, the lenders don’t have to go through the court system, which can significantly cut down on the lengthy foreclosure timeline. Now, the borrower can usually get the courts involved if they so choose, but they’ll most definitely need the help of an attorney to make that effective.

To figure out if, in the event you don’t pay your mortgage, you’ll be subject to a judicial or non-judicial foreclosure, review your mortgage paperwork you worked out with the lender. If it contains a power of sale or if your loan is based on a deed of trust, that means the lender can begin the foreclosure process non-judicially, but that doesn’t mean you can’t make it judicial at a later date via filing a lawsuit.

The Foreclosure Process

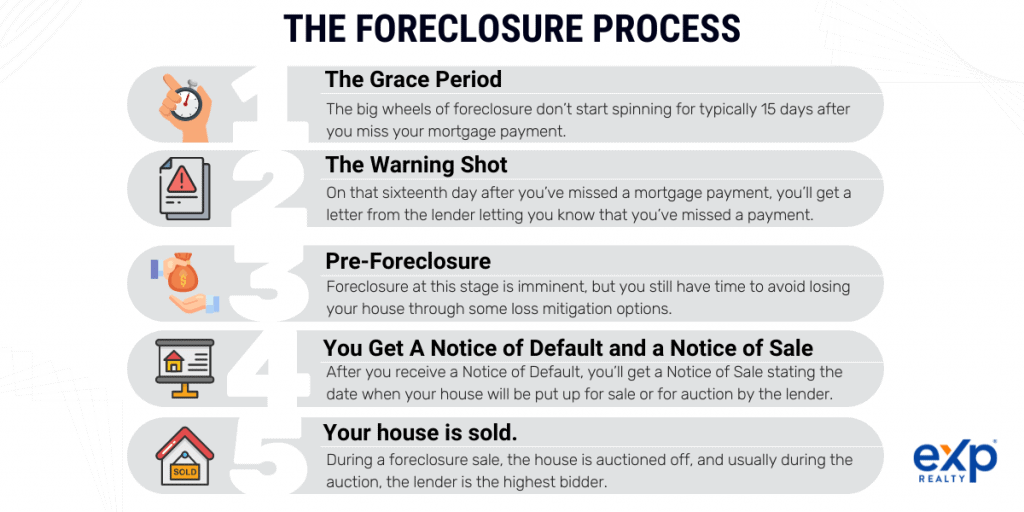

Step One: The Grace Period

If you miss a payment by a few days, either because your paycheck didn’t line up with the payment date, or you had to unexpectedly pay for something expensive, don’t panic. The big wheels of foreclosure don’t start spinning for typically 15 days after you miss your mortgage payment (although you can be up to 120 days late in payments before the real foreclosure process begins). Past this point, if you know for a fact that you won’t be able to pay your mortgage during those fifteen days, go ahead and contact the lender now and let them know while time is still on your side.

Step Two: The Warning Shot(s)

On that sixteenth day after you’ve missed a mortgage payment, you’ll get a letter or some form of contact from the lender letting you know what you already know: you’ve missed a payment. If you pay your mortgage during this phase, you’ll probably be charged a late fee, which is still much better than getting your home foreclosed on, but that’s still a way down the line at this stage of the process.

Typically the lender will give you a specific date and sum to be paid along with that warning letter. More often than not your lender will let you catch back up (with fees). If you’re certain there’s no way you can keep paying your mortgage, hire a lawyer if you can and start planning on negotiating what is called loss mitigation options, i.e. ways to satisfy the lender without them foreclosing on your home. We’ll cover these in step three.

Step Three: Pre-Foreclosure

Foreclosure at this stage is imminent, but you still have time to avoid losing your house through some loss mitigation options. Let’s review a few of these.

Forbearance: If you’re truly in dire financial straits, try to get a forbearance on your mortgage. With forbearance, the lender will no longer require you to make payments for a specified amount of time, giving you a chance to fix your finances and build up some savings. Forbearance won’t hurt your credit any more than it has already been hurt because you’re not missing your payments. Forbearance doesn’t get rid of those payments you’re putting off either, just pushing back the date you need to pay them by. If you’re negotiating loss mitigation options with your lender, it might be best to get forbearance first to stabilize your credit and your finances while you negotiate future options like a loan modification or refinancing. You can qualify for forbearance if you have a federally-backed mortgage, such as a VA or FHA loan.

Loan Modification: Put simply, you can renegotiate the amount you pay per month, usually at the cost of extending the timeline of your loan. Though you’ll be paying more over the long term, the lender will take smaller bites out of your income at a time, which can help you hopefully get back on your feet. Though this will hurt your credit initially, if you’re able to make payments on time after this, it will help in the long run.

Short Sale: Put simply, a short sale is where you sell your home for less than it’s worth in order to pay off some of your mortgage debt. 99.9% of the time short sales absolve all of your debt. However, sometimes there is still money left over that you owe to the lender, called a deficiency. If the lender can get a deficiency judgment in their favor, they’ll be able to collect their debt from you by wage garnishment (your employer will set aside a percentage of your wages/salary to pay the bank) or by levying your bank account, i.e. the lender will draw the required funds from your bank account.

Deed in Lieu of Foreclosure: This isn’t so much a remedy as it is a last resort option, a painkiller. If you go this route and negotiate a deed in lieu of foreclosure, the lender will still take possession of your house, but you can get out of paying the rest of your debt. Obviously, this is nobody’s first choice, but it is still an option. Be sure to get it in writing, as a waiver, that the lender will waive your deficiency if you go with the Deed in Lieu of Foreclosure option.

A deficiency is the amount of money you’d still owe the lender. If you can’t get your deficiency waived, you’ll still have to pay back the lender after transferring the title, which would defeat the purpose of them forfeiting the foreclosure.

Step Four: You Get A Notice of Default and a Notice of Sale

If all negotiation fails and you’re unable to pay your mortgage within the time frame set during the loss mitigation period of Pre-Foreclosure, the true foreclosure process will begin. First, the lender will send a notice of default to the appropriate civic authority, typically the county recorder’s office, and, depending on which state you’re in, that notice of default will also be sent to you.

Either simultaneously or right after this Notice of Default, you’ll get a Notice of Sale stating the date when your house will be put up for sale or for auction by the lender. Now, in the time between the Notice of Default and Sale and the actual selling of your home, you can still live in your home and you still have the chance to pay off your debts to ‘cure’ the default. If you can’t cure the default in this allotted time, which in a judicial foreclosure can be several months and a non-judicial foreclosure can be significantly less time, your home will be sold.

Step Five: Your house is sold.

During a foreclosure sale, the house is auctioned off, and usually during the auction, the lender is the highest bidder as they use your existing debt as a credit to buy the house. In some states, this is the end of the road for the homeowner. In others, there’s still one more chance to get your home back.

(possible) Step Six. The Post-Sale Redemption Period

Even after your home has been sold, some states allow you to remain in the house for a set period of time in which you can even buy your house back from the lender or whoever else bought it. Depending on the state, the Redemption Period goes into effect either before or after the Sale of the house, and in some cases takes effect through the sale process. Most states allow redemption periods with certain caveats. It’s more useful to list the states that offer no redemption periods for foreclosed homeowners. They are:

- Delaware

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Indiana

- Louisiana

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- Nebraska

- New Hampshire

- New York

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Utah

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

Everywhere else, you have a shot at redeeming your home.

If you find you find yourself unable to pay your mortgage, don’t despair. There are options out there to stop the foreclosure process and keep your home. In many cases, you have years to work out negotiations with your lender, and with a good lawyer and some patience, you can stay in your home and rescue your credit score. To learn more about your state’s homeowner rights and get more advice on foreclosure, check out usa.gov/foreclosure.